The

Brand Plays On (The Observer Magazine 2nd February

2003)

Daddy G is on paternity leave and Mushroom has been left in the

dark. But thanks to 3D's vision, Massive Attack has finished another masterpiece.

Interview by Sean O'Hagan. Photographs by Warren Du Preez & Nick Thornton

Jones.

The solo album used to be one of the great conceits of the 70s rock group. When

a lead singer or guitarist booked studio time to 'do his own thing', it usually

signalled not so much the pursuit of total creative freedom, but the imminent

disintegration of the group in question. Today, things are not so simple. For

a start, a pop group can be anything you want it to be, from a DJ (Fatboy Slim)

to a concept (Gorillaz) to a prepackaged commodity (The Cheeky Girls). Or, and

this is where things can get really tricky creatively and financially, a collective.

Take Massive Attack, for instance. From the start, by design, they were never

a proper pop group at all, more a loose, constantly shifting aggregation of

like-minded souls who adhered around a core membership of three oddball Bristolians:

Robert '3D' Del Naja, Grant 'Daddy G' Marshall and Andrew 'Mushroom' Vowles,

none of whom could sing or play a 'proper' instrument.

Bonded by a love of hip-hop, and a determination to, as Del Naja once succinctly

put it, 'avoid the obvious at all costs', Massive Attack were always an emphatically

modern pop entity: an idea, a brand even, but never simply a group. It is intriguing,

then, that 100th Window, their imminent fourth album is, in effect, a solo venture,

written, co-produced, art directed, and performed by Robert Del Naja. (Though

it does feature the familiar voice of long-term floating member, Horace Andy,

a veteran Jamaican reggae singer of the Rastafarian faith, as well as new guest

vocalist, Sinead 0'Connor, a recent Irish convert to the same.) For the second

time in their influential 15-year career, though, the names that are absent

from the credits are perhaps more revealing than the one(s) remaining.

Missing in action are Mushroom, the most effortlessly oddball member, who departed

the band under somewhat hazy circumstances fol- lowing the release of their

previous album, Mezzanine, in 1998. More surprising still is the absence of

Daddy G, who opted to spend quality time with his newborn daughter rather than

hang around the studio waiting for the muse to turn up. Officially, Daddy G

is still a member of Massive Attack: he features on all the publicity shots

for the album, and looks likely to perform on their forth- coming tour. The

word, off the record, though, is that he is still considering whether or not

to re-enter the fold full-time. For the time being, at least, Massive Attack

is Robert Del Naja.

'I guess it seems odd to people who don't know us that we seem to mutate and

continue like some strange mutant creature,' he muses, tucking into room service

Lebanese tapas, while keeping a keen eye on his beloved Bristol City, who are

making a rare appearance on Sky Sports. We are talking in his room in the Mandarin

Oriental hotel in Knightsbridge. 'From the start, though, the idea was to be

as different as possi- ble to the traditional rock group. We came up through

hip-hop and that whole sound-system ideal where the' crew is everything. Plus,

we had to adapt and change just to survive.' You seem, I venture, to have slimmed

down in order to survive. 'Yea. Funny that,' he laughs, evasive as ever. 'In

retrospect, I did think that the line-up on the first album [the ground-breaking,

and still startling, Blue Lines from 1987] would stay together. Then, suddenly,

Shara [Nelson, singer] went off to do her own thing. Then Tricky [rapper] flew

the coup. Good luck to them, too. But, then we lost our manager-cum-producer

[Cameron McVey] because he was off working on his wife's [Neneh Cherry] second

album, which took forever. That threw us a bit, and ever since, to tell the

truth, it feels like starting over every time we do an album. This time, it

was me starting over on my own. It was terrifying, but liberating.'

Del Naja is someone who speaks as he thinks: in conversational surges that are

both finely detailed and oddly evasive. He comes across as the polar opposite

of the stereotype that dogs Bristol musicians, being neither a stoner nor a

slacker, but hyper and intense. All the evidence would suggest that he is the

Machiavelli behind the Massive Attack game plan, someone who tends to get his

way in the battle of wills that is an inevitable part of the creative dynamic

of any so-called pop collective.

He seems to have grasped early on that the notion of creative democracy seldom

works in a pop group, however loose and non-traditional that pop group may be.

'We were all incredibly stub-born individuals,' he continues, cracking open

a beer, 'and there was always this tension between control and collaboration.

Always. Then, around Mezzanine [their last album, released to a mixed response

in 1998], it became a battle over direction. I wanted to bring in elements of

New Wave - the stuff that influenced us just as much as hip-hop. I know everyone

says, "Oh Mezzanine was Del Naja's album,

he wanted the guitars, he's a control freak." But, from the start, the

plan was to tear up the blue-print with every album.'

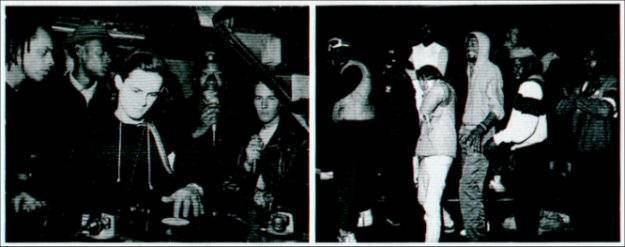

Wild west: (above, from left) Milo, Daddy G, Nellee, Willie Wee and 3D in the

Dug Out DJ's booth; and the B-Boy Crew at a Wild Bunch jam at the Thekia - both

in Bristol in 1985.

So, was it the sudden move

towards a more 'rock' sound that precipitated Mushroom's departure? There's

an uncharacteristically long pause, 'Well, Mush is a purist,' he says finally,

diplomatically. 'He's into his soul and funk and hip-hop, There was tension,

definitely.'

This is understating the case somewhat. The word on the Bristol and London grapevines

back then was that Mushroom was unhappy way before Mezzanine, and had been vehemently

opposed to Del Naja's decision to bring erstwhile Soul II Soul member, Nellee

Hooper, on board as producer of the previous album, 1994's Protection. To make

things even more incestuous, Hooper had been ar original member of the Wild

Bunch, the Bristol hip-hop collective out of which Massive Attack Tricky and

Geoff Barrow of Portishead all graduated. When I put this version of events

to Del Naja he grows guarded. 'Aw man. I'm not sure I should get into this.'

In the public interest - or at least that discerning element of the public who

conside Massive Attack a British pop-cultural treasure -press him further. 'I

suppose Mushroom got very pure about it all. He didn't really trust Nellee to

do it, I guess. Then, after a while, he didn't want me and G to touch his stuff

either. It got to where if he didn't like the way something was going, he'd

just stop working on it. It forced me into a position of working with Nellee

on other tracks. It was personality battles all the way. With three people,

ther will always be a decision. When you have four, it gets complicated.'

And with one, of course, you get your own way Biting the bullet, I ask if Mushroom

was pushed or did he jump? 'It wasn't that black and white,' he says. 'None

of us were really communicating on Mezzanine. We were just trying to get the

job finished, which is why, when I hear it now, usually in the background on

late-night TV programme about serial killers, it feels really cold to me. Mechanical.

We weren't dealing with emotions. If we'd started discussing stuff for real,

and collaborating properly and spiritually on the music, it would have all kicked

off.'

It finally did kick

off the following summer, just after the group had finished touring Suddenly,

as Del Naja puts it 'there was no itinerary to tell you what you were going

to do the next day, when you were going to meet the boys again. So we didn't

meet for a while. We just drifted off. That's when me and G felt, "What's

going on here? We're not happy."'

Mushroom's departure, when

it finally came in the summer of 1999, was, according to Del Naja, and contrary

to the rumours that were flying around at the time, not acrimonious but oddly

'clinical... It was all done on the phone. Very cold, really horrible.' He shakes

his head, looking and sounding genuinely regretful. 'Everything became thinner

and smaller. All that warmth being spun into a tiny little thread, then that

thread just being cut.'

Mushroom is now pursuing

his own presumably more purist project, which has the working title, Champagne.

I tried ringing him a few times on his old home number, but there was no answer.

When I spoke briefly to Daddy G on the phone, he said he had not spoken to,

nor seen, the wayward studio genius for a few years. Nor, it seems, has anyone

on the Bristol scene. He was last spotted in New York, where, intriguingly,

both Tricky and another original Wild Bunch member, Milo, are also based. I

ask Del Naja if he misses the man many regard as the group's temperamental lost

genius. He nods. 'I heard recently from a friend that he was softening, he was

speaking more positively about me, so, who knows, maybe we can make it up.'

I would be intrigued to hear

what Mushroom makes of the new Massive Attack album, 100th Window. 'It's that

part of your mind that you can't close, that stays open at night for intruders

to enter. It's also the window you can never close on your computer, the one

that lets intruders in there, too.' The record sounds different enough to offend

any remaining purist fans longing for a return to the rootsier, dub-driven,

electric-soul sound of old. It is electronic in both the literal and generic

sense of the word, dark, brooding, and possessed of a slow-burning cumulative

power that is insidious rather than immediately arresting. A record that you

have to live with for a while and that, even bv their con- sistently tortuous

standards, was a protracted and difficult birth. Initially they recorded over

80 hours of what Del Naja calls 'sonic jams' with Lupine Howl, a Spiritualised

offshoot now based in Bristol. Unable to condense all that work into manageable

tracks, they promptly ditched most of it - only two songs survive - and started

again from scratch. If there is nothing here as startlingly epic as 'Unfinished

Sympathy', nor as sparsely powerful as 'Protection', the songs still sound singular

and stirring, not least when Sinead O'Connor unleashes the full-throated power

other pristine voice on 'Prayer For England', a characteristically impassioned

plea for an end to violence against children, whether sexual, institutional

or political.

'How many people are out

there who convey total honesty and really say what they think in this game?'

enthuses Del Naja, who first met the feisty Irish

singer when they both appeared on Top of the Pops more than a decade ago. 'I

wanted to work with someone who was honest above all else. We tried loads of

people over the years. It's hard to find a personality now. Sinead is utterly

real.' And, she certainly brings something new to the mix, a heartfelt spiritual

directness that finds its purist form on 'What Your Soul Sings'. Like previous

guest vocalists, Liz Frazier and Tracy Thorn, O'Connor also finds a renewed

freedom of expression working in the new context that Massive Attack seems to

unerringly provide for voices we think we have grown utterly familiar with.

When I ask Del Naja who he would like to work with in the future, he answers

with a swiftness that suggests he has already given this some considerable thought.

'Aaron Neville. His voice makes my teeth melt. We wanted to work with Nina Simone

on this album, and we tracked her to the south of France. Then, this force field

came down. I think we may hook up with Tom Waits in the future. Who knows?'

He pauses to light a cigarette and grab another beer from the mini-bar. 'I'll

tell you something funny. We thought about working with Chuck D [Public Enemy's

lyrical polemicist] years ago. And Rakim [the 80s rapper against whom all other

rappers are still measured]. But, you know what? Me and Tricky were too proud.

It was like, "We do the rapping around here." Rakim, for Christ's

sake, the don!'

It was inevitable that Tricky's

name would crop up. Like Mushroom, the maverick lyricist seems to have disappeared

from view of late, having long since departed the Massive Attack fold in equally

mysterious circumstances somewhere between the release of Blue Lines and Protection.

I ask Del Naja if he ever thinks back to the old days when the Wild Bunch -

himself, Tricky, Hooper, Daddy G, Mushroom, the mysterious Milo and the even

more mysterious Claude - were simply a bunch of talented chancers on the fledgling

Bristol hip-hop scene. 'Yea, man! It's just beautiful nostalgia though, ain't

it? Largly twenties, living with Tricky. Both Aquarius. Both stubborn and opinionated

as fuck. That,' he cackles, 'was another implosion waiting to happen.'

The pre-irnplosion magic

is captured to a degree on the CD compilation, The Wild Bunch: Story of a Sound

System, compiled by the aforementioned Milo. There, on seminal songs like their

sparse, bass-heavy restruc- turing of Bacharach & David's ballad, The Look

of Love', you can hear the seeds of at least two ensuing genres: the

dub-heavy hip-hop soul sound that came to fruition in the late 80s with Blue

Lines and those early Nellee Hooper produced Soul II Soul singles, 'Back to

Life' and 'Keep on Movin"; and the hypnotic, narcotic pulse of what would

come to be known as trip-hop - everything from Tricky to Portishead to Morcheeba.

The sound of young Bristol in full-effect sounds both 'beautifully nostalgic'

and oddly timeless.

Nearly 20 years on, the collective

ideal that underpinned that seminal song has, it must be said, taken a drubbing

at the hands of competing egos and conflicting ambitions, despite Massive Attack's

best intentions to the contrary. Their progress, at times, has been Darwinian:

they have shed crucial members, lost a manager and a studio, and been successfully

sued by two old-school rock performers - John McLaughlin, whose voice was sampled

without clearance on Unfinished Sympathy and Manfred Mann, one of whose bass

lines underpinned Mezzanine's 'Black Milk'. 'I'm not going to get all bitter

and twisted,' laughs Del Naja, 'but G and Neil [Davidge, a long-time studio

collaborator] were dealing with it - we always declare samples - and I was told

it was just a bit of atmosphere. It turned out to be the whole bass line. So,

we got fucked for that.'

What causes Del Naja even

more regret, though, is the memory of how they were cajoled by the record company

and management into dropping the second part of their name in order to garner

airplay during the Gulf War, when, ludicrously, the conjunction of Massive and

Attack was judged unpatriotic by the self-censoring tsars at the BBC. These

days, Del Naja is one of the few voices of organised protest within pop against

the imminent war with Iraq. Alongside Darnon Albarn from Blur, he has organised

the 'Don't Attack Iraq' campaign, personally paying for campaigning adverts

in the music press. 'It's been hard to get people on board,' he sighs, obviously

aggrieved. "No one wants to stand up and be counted in case it loses them

American sales. That's where we live right now.' Has he garnered much support

from fans? 'Well, initially, we had loads of flak on the website from irate

American Massive Attack fans, but it's not anti-American, it's anti-administrationism.

The tide has turned since, though, and now there are more messages of support

from American fans, as well as musicians and artists, than British ones.'

So continues the adventures

of Massive Attack, a collective idea that seems somehow to have survived even

its reduction to a single core member. The group's reputation for originality

and innovation looks set to remain intact, too, with the release of the promo

video for 'Special Cases', which takes the form of a computer-generated corporate

video for a company specialising in the genetic cloning of humans. Ironically,

no humans appear in the video, not even to lip-sync the song. On film, if not

in the flesh, Massive Attack have momentarily disappeared from view altogether.

Is this, I wonder, a metaphor for the future?

' Nah, that's going way too

deep,' he laughs, opening another beer. 'Massive Attack is an entity. It's ambiguous.

Always was. That's why we had symbolic images like the flame. Symbols rather

than faces, so that it's not just about people. I've always thought that the

best way to do something with longevity was not to attach a face to it, not

to make it about people on a record sleeve or posters.I guess we were into rebranding

long before it became known as that. Every album was a whole new concept released

under an identifiable name. We were always ahead of our time, even if we didn't

know it. That's something.'

It sure is. Massive Attack

could yet confound all expectations and grow old gracefully. Or they could simply

and slowly fade from view, another implosion just waiting to happen. We'll have

to wait and see but, with Del Naja at the helm, I'd bet money on the former

option.

For the record (The Observer Magazine 9th February 2003)

Our OM piece last week on the band Massive Attack was wrong to say of Grant Marshall that 'off the record, he is still considering whether or not to re-enter the fold full time'. He has asked that we make it clear that he is still a full-time member of Massive Attack. We apologise for any misunderstanding.